Why Measure Food Loss and Waste? - Why and How to Measure Food Loss and Waste

A significant amount of food grown for human consumption is never eaten. In fact, by weight, about one-third of all food produced in the world in 2009 was lost or wasted (FAO 2011). In North America, approximately 168 million tonnes of FLW are generated annually: 13 million in Canada, 28 million in Mexico and 126 million in the United States. This equates to 396 kilograms per capita in Canada, 249 in Mexico and 415 in the United States (CEC 2017).

This level of inefficiency suggests three strong incentives to reduce food loss and waste: economic, environmental and social.

Economic: The huge amounts of food lost or wasted are currently considered part of the cost of doing business as usual. Rather than trying to maximize the value of food produced, companies and other organizations tend to focus on the disposal costs for the products that are lost or wasted. Companies could make significant economic gains by putting food headed for the waste stream to profitable uses.

Environmental: When food is lost or wasted, all of the environmental inputs used on that food are wasted as well (FAO 2011). That means all the land, water, fertilizer, fuel and other resources that produced, processed or transported a food item are wasted when food meant to be consumed by people is thrown away. Food waste sent to landfills creates methane – a powerful greenhouse gas. Thus, reducing FLW can reduce a company’s environmental footprint.

Social: Surplus edible food can be redistributed to food banks, food rescue agencies and other charities, which can direct it to food insecure populations, making good use of the food rather than disposing of it. For many companies, food donation or redistribution is an important part of corporate social responsibility activities. Food directed to human consumption is not considered to be lost or wasted.

The old adage that “what gets measured gets managed” holds true with FLW. Measuring food waste helps an organization understand the root causes of food waste and thus work to prevent it.

The Risk of Not Changing

The business-as-usual path has risks. If a company continues to operate with built-in assumptions about acceptable levels of waste, it risks being surpassed by its more innovative competitors who can turn waste into profit. The business case for reducing FLW is strong, and those who ignore this opportunity will continue to waste money and resources. Additionally, an increasing number of local, subnational and national governments are imposing disposal bans on food waste or requiring excess food to be donated (Sustainable America 2017; Christian Science Monitor 2018). If this trend continues, companies may face increased expenses from further regulations in the future.

The Food Recovery Hierarchy

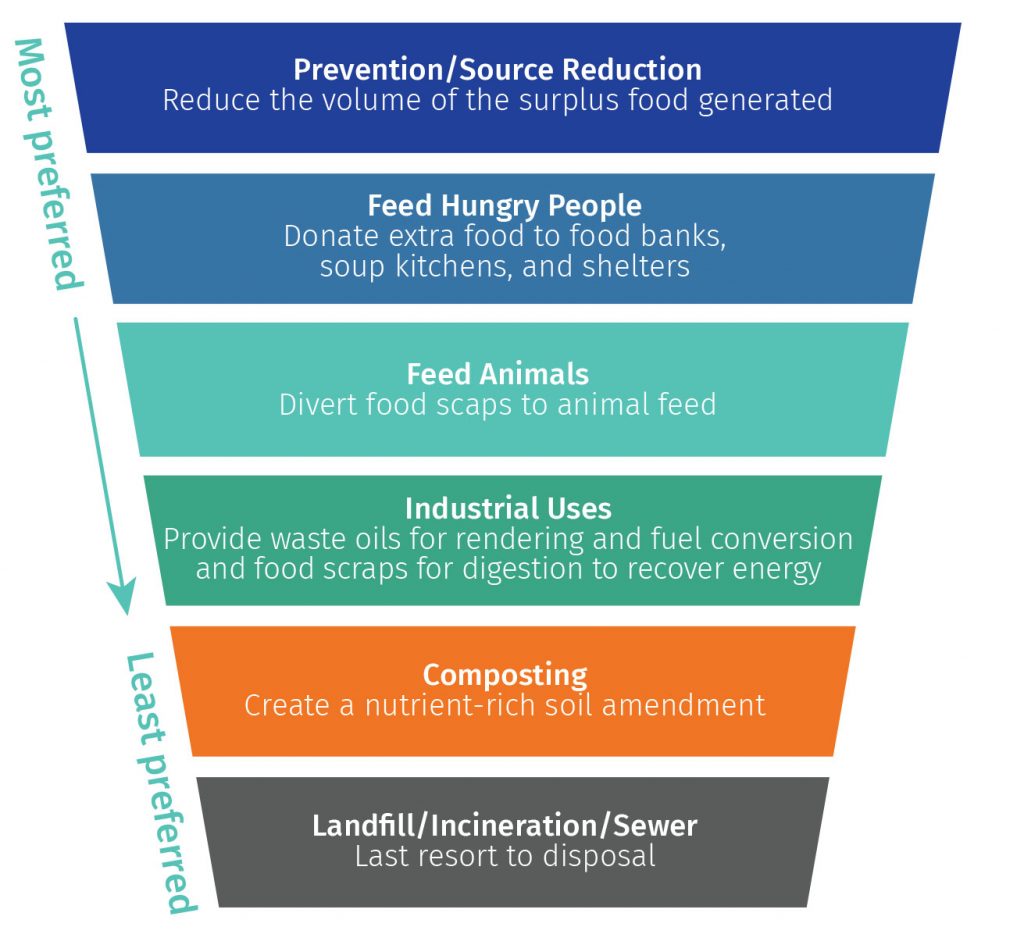

When trying to reduce FLW, the first emphasis should be on prevention, or source reduction. Although some end-of-life destinations for FLW have fewer negative impacts than others (e.g., FLW going to animal feed is preferable to FLW going to a landfill), prevention should be the foremost goal. This principle is reflected in the Food Recovery Hierarchy (Figure 1) developed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA).

Figure 1. Food Recovery Hierarchy

Source: Adapted from US EPA n.d.

Source reduction (i.e., preventing food waste in the first place) is the most desirable way to address FLW because it prevents the negative social, environmental and economic impacts of producing food that is wasted. Moving down the recovery hierarchy stages, less value is recovered from the FLW at each stage, until the bottom stage —landfill, incineration or sewer disposal—where negative environmental impacts are highest. From a climate perspective, tonne for tonne, preventing wasted food is six to seven times as beneficial as composting or anaerobic digestion of the waste (US EPA 2016).